Modern philosopher Paul Tyson asks in a paper "Can Modern Science be Theologically Salvaged ?”

Not really. He reflects on Conor Cunningham’s brilliant book, Darwin’s Pious Idea, which is to date the finest reconciliation of evolution with serious, philosophically informed orthodox Christianity…but, in the end, says Tyson, modernity and liberalism have rendered science too metaphysically bankrupt to hold real Truths.

Here are some fine extracts from the essay HERE

Not really. He reflects on Conor Cunningham’s brilliant book, Darwin’s Pious Idea, which is to date the finest reconciliation of evolution with serious, philosophically informed orthodox Christianity…but, in the end, says Tyson, modernity and liberalism have rendered science too metaphysically bankrupt to hold real Truths.

Here are some fine extracts from the essay HERE

….scientific knowledge is modernity’s functional metaphysics and that modernity’s metaphysical integrity—and this is not science itself—is intellectually moribund.For within a frame of belief premised on the acceptance of an entirely immanent nature and on the nominalist subject’s internally situated epistemological capacities, the modern knower can have no certain knowledge of objective reality. So the modern approach to truth—having turned its back on faith, participation, revelation, and certainty—redefines truth to mean, not a genuine knowledge of reality, but rather a probable and ever-revisable psycho- social construct which is only ‘true’ because it is instrumentally useful to us .

We have replaced reality with the legal fiction of empirical objectivity, and we have replaced truth with the instrumental criteria of pragmatic utility. Further, modernity has replaced meaning—a notion not amenable to the terms of empirical objectivity—with the syntax of language and with the epiphenomenal subjective belief-secretions of culture.

Thus modernity’s theoretical premises hold that truth and meaning are functions of power, use, and fiction. What truth really is, is instrumental power. What meanings really are, are imagined fictions that have some psycho-bio- social use when overlaid upon the meaningless objectivity of the world, understood in probabilistic, empirical terms.

…it is enormously philosophically loaded: all the terms of its materialistically reductionist methodology betray prior existential commitments and a set of assumed metaphysical, methodological, and epistemological assumptions.

For it is simply the case that truth and meaning cannot be functionally dispensed with if we are to remain, in normal, daily life, recognizably human. So idols must be fashioned out of tangible and controllable materials to stand in for truth and meaning so that we have something graspable to orientate value, choice, identity, and meaning in our lives. This collective worship—as with all public cultus— legitimates its way of life and upholds the continuity of its life-form over time. And it is the pseudo-scientists—those who speak in the name of science to tell us what the truth about reality is, what the real meaning of our lives is, and what our human values and cultural narratives really amount to—who are the priests of our secular, materialist public cultus.

Reducing reality to only having meaning within a reductively materialist metaphysical frame is a move that rests on an existential preference that entails the self-defeating implication that all existential preferences and metaphysical convictions must be equally meaningless.

As prior, one must have faith in them rather than seek to prove them in derivative terms. This modern urge for the proof of what Aristotle calls “the primitives” is at the core of modernity’s deep irrationality and intellectual futility. This modern refusal to ground reason in a living and grateful faith in meaning and truth is at the core of its hubristic folly and its hopelessly disintegrative approach to knowledge.

For where first philosophy comes before science, then the important questions of truth and value must not be determined by science, but rather the use and meaning of science must be determined by theology—that is, by a divinely revealed, analogically framed apprehension of real reality.

….our culture’s commitment to liberalism in relation to religious beliefs—the privatisation of religious belief itself—means that practically, it is only meaningless and merely instrumental ‘facts’ that we now can collectively believe in as publically true.

Science is never just science to us moderns, but it is the integral public discourse of modern liberalism. Modern liberalism says that science is one thing—just about value neutral facts—and each person, be they religious or not, interprets the meaning of their own subjective experiences and decides what values they will embrace entirely on the grounds of their own freedom of conscience.

I cannot see that Christianity can do without the belief that the whole of nature still needs radical redemption. I find I cannot dispense with the Pauline notion that the whole of creation was subjected to futility by sin and is in travail waiting for its full redemption, and the church is the sacrament and foretaste of this radical eschaton in which all of material reality is to be caught up.

Yet the idea central to modern scientific natural history is that things have always been the way they now are, from the lifeless and meaningless beginning of time so many billions of years ago, and will always be this way until the equally lifeless and meaningless end of time, so many billions of years hence. Modern naturalism recognizes only one age, only one nature. Life is a strange and transitory visitor in such a picture of reality. Without some sort of true meaning to Eden, the radicality of goodness in creation, which persists but is marred by sin, death, scarcity, and disease, is lost, and the radical eschatological horizon of total redemptive hope for nature is also lost.

If we are to hold onto any real notion of Eden we cannot simply accept the one age, one nature view basic to modern naturalism. But any real notion of Eden cannot be understood in scientific terms; there can be no recourse to Creation Science here. For the logic of fundamentally different orders of nature which are at the alpha and the omega of the biblical narrative makes any prelapsarian order of nature as inaccessible to the knowledge categories of the present natural order as is the post-eschaton natural order.

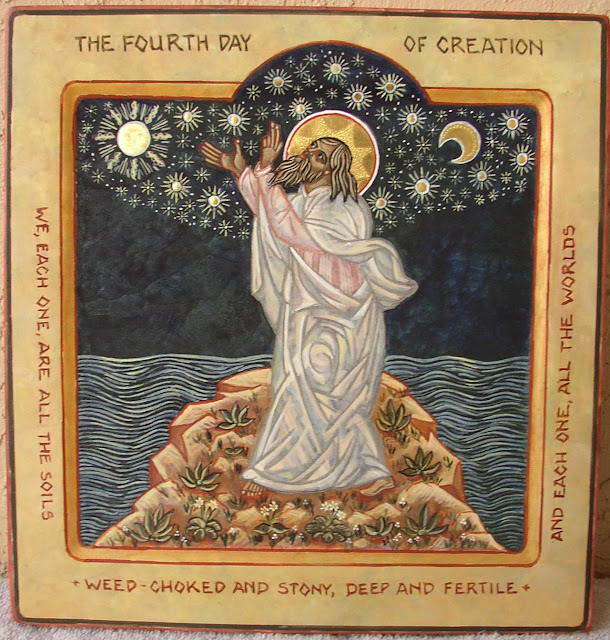

This logic of different natural orders is, for all intents and purposes, the same as the logic of alternative universes. Hence myth and irreducibly symbolic imagery are the only revealed access we have to both of those ages (or different universes).

This logic of different natural orders is, for all intents and purposes, the same as the logic of alternative universes. Hence myth and irreducibly symbolic imagery are the only revealed access we have to both of those ages (or different universes).

So it cannot be avoided that any commitment to Eden and to different natural orders is going to be a stumbling block to the one age/nature assumption of natural history, which is simply presupposed by modern science. Equally, any reduction of Christian doctrine in order to fit a one age/nature understanding of natural history is going to render the cosmogenic, cosmological, and teleological tropes of Christian belief’s sacred narrative as having no actually true redemptive meaning for us who seek to inhabit this poignantly beautiful veil of tears in hope.

John Henry Newman has said :

John Henry Newman has said :

“It is not reason that is against us, but imagination... The ways in which we ‘see’ the world, its story and its destiny; the ways in which we ‘see’ what human beings are, and what they’re for, and how they are related to each other and the world around them; these things are shaped and structured by the stories that we tell, the cities we inhabit, the buildings in which we live, and work, and play; by how we handle – through drama, art and song – the things that give us pain and bring us joy. What does the world look like? What do we look like? What does God look like? It is not easy to think Christian thoughts in a culture whose imagination, whose ways of ‘seeing’ the world and everything there is to see, are increasingly unschooled by Christianity and, to a considerable and deepening extent, quite hostile to it.”

The imaginative landscapes of cosmogonies are very culturally powerful, and we should think very carefully before we concede truth to the assumptions of a modern, naturalistic cosmogeny.

Jacques Ellul, too—no fundamentalist by any measure—sees that in all our modern scientific sophistication, we cannot better the Genesis myth, and we do it a terrible injustice if we seek to interpret it in a manner compatible with modern science.

I suspect that modern science is too deeply embedded in a ‘one age’ imaginative mythos of originary contest and nihilistic materialism to contain insights compatible with the truths of Christianity.

Sociologically, modern science’s cosmogenic speculations, cosmological assumptions, and teleological nihilism, are foundational to modern liberalism and modern secular reason.

For these reasons I do not think modern science, as inextricably enmeshed with modernity as it is, can be accepted if one believes that Christ is the alpha and the omega of all that is, and if one is to think about nature and reality in the light of divine knowledge which is given (and hence nothing we own, possess, or stand over) to us by the grace of God.

I think we have a problem with the operational scope and methodological assumptions of modern science itself, and with the implicit natura pura frame of interpretation which cannot be simply extracted from modern science—and in the final analysis, I do not think modern science can be theologically salvaged.

* See Louise Dupré, Passage to Modernity, and Goetz & Taliaferro, Naturalism, 2008. The notion that there is a discrete nature and a discrete super-nature, and functionally only a ‘pure’ nature without any participation in a transcendent dimension prior to and beyond the directly tangible, is the functional foundation of modern science. Modern science works within this anti-metaphysical cosmology. This cannot be squared with any orthodox doctrine of creation. The science that is produced from within the operational framework of natura pura, then, should not be expected to align with Christian faith regarding the nature of nature, the meaning of human life, and the alpha of primeval goodness and the omega of redemptive glory which is the origin and teleology of creation as understood by the Christian faith.