Johannes Hoff’s The Analogical Turn: Rethinking Modernity with Nicholas of Cusa is remarkable, he posits an “alternative modernity” in which Renaissance accounts of space, perspective, and perception leads to modernity’s narcissistic hyperreflexity, and use of analytic rationality and individuality. He instead offers Cusa’s doxological epistemology” - doxology = right praise - where one loves to know.

Here is a part of John Betz’s take on the book, and a snippet of Hoff’s response, found HERE :

“…modern dialectics have blinded us to reality—either in the way that modern scientific rationalism tries to extort from creatures a univocal meaning they have never had, or in the way that postmodernism denies that creatures have any intrinsic meaning at all that is not a function of culture, the will to power, or the play of différance. In short, both of these extremes—“the univocity of modern scientific rationality and the ambiguous equivocity of post-modern pop culture” (xv)—have rendered reality opaque. And so we need to go back to Cusa’s analogical rationality if we are to go forward into an apocalyptic future in which the world will be seen for what it is, a transparency of divine things, and one can “see in every creature an image of the divine amabilitas”

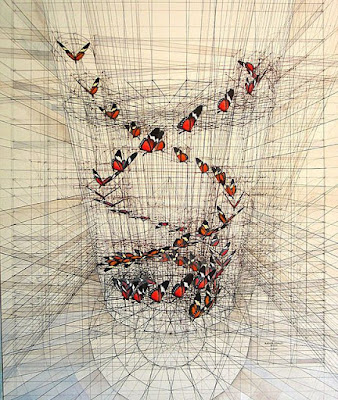

Hoff traces back to the work of Cusa’s contemporary and fellow priest, Leon Battista Alberti (1406–72), who “applied the mathematical methods of Euclid to the art of painting” . On the face of it, there does not seem to be anything problematic here: Alberti’s mathematical mapping of perspective can subsequently be seen in the geometrical art of Piero della Francesca, who is best known and admired for his paintings of gospel scenes (e.g., The Baptism of Christ from 1450). Nevertheless, Hoff sees a problematic turning point here that will subsequently define the “world picture” (in the Heideggerian sense) of the modern age.

The problem, as he sees it, is that the vanishing point of the work of art mirrors that of the viewer, eo ipso “putting the latter in the position of a sovereign observer who can control the space of his perception as if it were nothing but a mirror image of his subjective position” (48). In other words, from this point on, Hoff argues, modern perspective is defined not by a “being seen” (as one is seen by the gaze of an icon) or by a misty seeing of the invisible through the visible—one could just as well say, of the infinite through the finite—but by the dominant viewer (the new and only topos noetos) and this viewer’s imaging of reality in narcissistic terms, according to his conception of it. In short, reality is now configured in my image and according to my representation of it. Thus, according to Hoff’s genealogy, the “winged eye” of Alberti (which appears on the flipside of his portrait medallion) leads directly to the “thinking I” of Descartes’s cogito —and thence, one might add, to the synoptic transcendental ego of Kant.

At this specular point a distinctly modern perspective is established (which for Hoff is also the presupposition of modern individualism).

.....the symbolic universe of the Middle Ages gives way to the “digital universe of Descartes and Leibniz” . Corporeal entities, as for Descartes, come to be regarded as “nothing but ‘extended things’ (res extensae) that can be represented analytically, based on functions and equations, without remainder” (; and so, inspired by visions of a mathesis universalis, matters of symbolic concern are “pushed aside in favor of simpler strategies of scientific progress”

Thus, as Hoff keenly observes, it was ironically modern artistic innovation...

.....he nevertheless maintained that “mathematical comparisons can only provide us with conjectures and not precise descriptions of our analogical world” (67). In other words, anticipating Kurt Gödel mutatis mutandis by nearly half a millennium, Cusa argued that because the world is structurally analogical, and opposites coincide in God alone, an exhaustive mathematical account of reality is impossible. In short, nothing can be pinned down and mastered; the Continental, Hegelian desideratum of a complete system and the Anglo-American desideratum of a final analysis are equally impossible.

At this specular point a distinctly modern perspective is established (which for Hoff is also the presupposition of modern individualism).

.....the symbolic universe of the Middle Ages gives way to the “digital universe of Descartes and Leibniz” . Corporeal entities, as for Descartes, come to be regarded as “nothing but ‘extended things’ (res extensae) that can be represented analytically, based on functions and equations, without remainder” (; and so, inspired by visions of a mathesis universalis, matters of symbolic concern are “pushed aside in favor of simpler strategies of scientific progress”

Thus, as Hoff keenly observes, it was ironically modern artistic innovation...

.....he nevertheless maintained that “mathematical comparisons can only provide us with conjectures and not precise descriptions of our analogical world” (67). In other words, anticipating Kurt Gödel mutatis mutandis by nearly half a millennium, Cusa argued that because the world is structurally analogical, and opposites coincide in God alone, an exhaustive mathematical account of reality is impossible. In short, nothing can be pinned down and mastered; the Continental, Hegelian desideratum of a complete system and the Anglo-American desideratum of a final analysis are equally impossible.

For in our world, in which everything is “enmeshed in the comparative logic of excedens (exceeding) and excessum (exceeded), of larger and smaller” (68), “nothing has the analytic ‘property’ [of being] one with itself. We may make rational conjectures about the identity of individual substances, but they are never analytically precise”

..

Whereas, on the modern model, which funds “the liberal societies of the modern age,” “every singularity is identical with its essence” and thus a “one” unto itself, for Cusa “nothing but God is One and identical with itself” .

....but, as Hoff notes, as analogical singularities, “the uniqueness of created individuals is neither analytically accountable nor conceivable as a ‘property’ that creatures ‘have’” . Rather, “the miracle is that every creature and every person is a singularity, not despite, but exactly because it owes everything it is to a giver whose perfections cannot be owned” . Indeed, rather than being one’s own property, according to Hoff’s Cusa-inspired metaphysics I cannot but “receive the gift to be one with myself” .

But, once again, such a metaphysical vision is inaccessible to the modern man, who is immured in his modern perspective—the perspective of “the modern Narcissus,”1 who puts himself “in the position of the eye point of a mathematically generated picture” , and precisely thereby makes his eye unreceptive to the light of the vision of God. As Hoff puts it, quoting Kleist, “it’s just a pity that the eye molders that is called to the vision of glory"

- John Betz

..

Whereas, on the modern model, which funds “the liberal societies of the modern age,” “every singularity is identical with its essence” and thus a “one” unto itself, for Cusa “nothing but God is One and identical with itself” .

....but, as Hoff notes, as analogical singularities, “the uniqueness of created individuals is neither analytically accountable nor conceivable as a ‘property’ that creatures ‘have’” . Rather, “the miracle is that every creature and every person is a singularity, not despite, but exactly because it owes everything it is to a giver whose perfections cannot be owned” . Indeed, rather than being one’s own property, according to Hoff’s Cusa-inspired metaphysics I cannot but “receive the gift to be one with myself” .

But, once again, such a metaphysical vision is inaccessible to the modern man, who is immured in his modern perspective—the perspective of “the modern Narcissus,”1 who puts himself “in the position of the eye point of a mathematically generated picture” , and precisely thereby makes his eye unreceptive to the light of the vision of God. As Hoff puts it, quoting Kleist, “it’s just a pity that the eye molders that is called to the vision of glory"

- John Betz

Now here is Hoff’s partial response to the above :

“The Cartesian promise that everything will straighten out if we only stick to the linear principles of representational security and analytical rigor has failed on every level of philosophical, mathematical and scientific research.

In the wake of thinkers as different as the early Romantics Ludwig Wittgenstein, Kurt Gödel and Martin Heidegger, we have learned that scientific reason is not reducible to true or false propositions.

I have outlined this more extensively in my publications on the necessity of replacing the radicalized phenomenological reduction (or epoché) of Foucault and Derrida by a “doxological reduction.”3 The above summary of Cusa’s method built on this research when it distinguished between two aspects of “truth” that interfere with each other and undermine every attempt to think in straight lines:

Our selection of true propositions (truth2) is regularly crossed by acts of wonder and praise (truth1) that guide our decisions about what deserves our attention and what does not.

If every knowledge starts with the commitment to a truth that transcends our reflexive comprehension, then it is no longer possible to draw a clear demarcation line between the straight lines of evidence-based, secure thinking patterns and the tentative, helical lines of walking paths that are sensitive to delusive shortcuts and attentive to performative indicators and narratives that structure the space that we inhabit.

As Michel de Certeau has pointed out, only subsequent to the fifteenth century did the “maps” that guide our cognitive and spatial movements become “disengaged” from the nonlinear “conditions of the possibility” of space.

( In another place, Hoff puts the matter like this, “…philosophers resisted the inclination to draw a clear demarcation line between the scientific cultivation of rational arguments and the religious cultivation of the symbolically charged spiritual practices that guide our attention”)

Cusa built on this Dionysian tradition—although he emphasized more than Albert (and in line with Aquinas) the unity of theology and philosophy: As in the case of doxological acts of prayer and praise, our intellectual power is a gift that we receive from the “father of lights.” And this gift is never received passively. Rather, the gesture of attentive receptivity coincides with the gesture of return: To receive the gift of the father of lights is tantamount with the realisation that my whole being is a gift that actualizes itself through acts of giving.”

- Hoff

“The Cartesian promise that everything will straighten out if we only stick to the linear principles of representational security and analytical rigor has failed on every level of philosophical, mathematical and scientific research.

In the wake of thinkers as different as the early Romantics Ludwig Wittgenstein, Kurt Gödel and Martin Heidegger, we have learned that scientific reason is not reducible to true or false propositions.

I have outlined this more extensively in my publications on the necessity of replacing the radicalized phenomenological reduction (or epoché) of Foucault and Derrida by a “doxological reduction.”3 The above summary of Cusa’s method built on this research when it distinguished between two aspects of “truth” that interfere with each other and undermine every attempt to think in straight lines:

Our selection of true propositions (truth2) is regularly crossed by acts of wonder and praise (truth1) that guide our decisions about what deserves our attention and what does not.

If every knowledge starts with the commitment to a truth that transcends our reflexive comprehension, then it is no longer possible to draw a clear demarcation line between the straight lines of evidence-based, secure thinking patterns and the tentative, helical lines of walking paths that are sensitive to delusive shortcuts and attentive to performative indicators and narratives that structure the space that we inhabit.

As Michel de Certeau has pointed out, only subsequent to the fifteenth century did the “maps” that guide our cognitive and spatial movements become “disengaged” from the nonlinear “conditions of the possibility” of space.

( In another place, Hoff puts the matter like this, “…philosophers resisted the inclination to draw a clear demarcation line between the scientific cultivation of rational arguments and the religious cultivation of the symbolically charged spiritual practices that guide our attention”)

Cusa built on this Dionysian tradition—although he emphasized more than Albert (and in line with Aquinas) the unity of theology and philosophy: As in the case of doxological acts of prayer and praise, our intellectual power is a gift that we receive from the “father of lights.” And this gift is never received passively. Rather, the gesture of attentive receptivity coincides with the gesture of return: To receive the gift of the father of lights is tantamount with the realisation that my whole being is a gift that actualizes itself through acts of giving.”

- Hoff