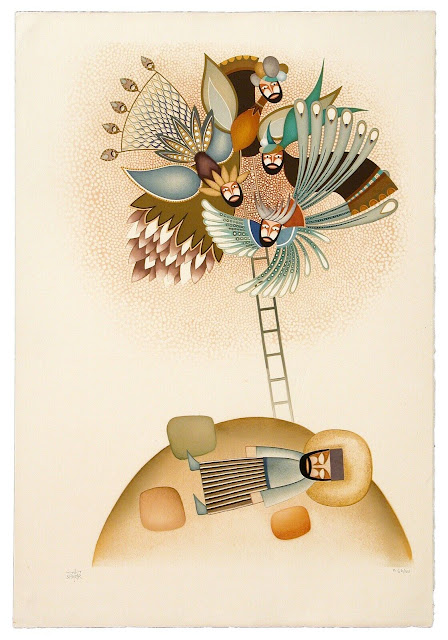

Recently a paper of mine was published, I have uploaded it on academia HERE and reproduced it below with very cool art work. Enjoy.

Liturgical mysticism: a Christian Theurgy?

Ritual deification in Orthodox Christianity and Neoplatonism

by

Jonathan McCormack

"Man is not satisfied with solutions beneath the level of divinization."

- Joseph Cardinal Ratzinger, 1

One usually thinks of ritual as antithetical to mysticism, yet in Neoplatonism we find the ritual practice of theurgy, or “god-work,” enacted to achieve henosis, union with the divine. As Pierre Hadot has pointed out, rather than intellectual analysis, philosophy for the ancients was a way of life, complete with chanting, prayers, and ascetic practice. It’s no secret Christianity has become an anemic, dying wraith in the West; yet in Orthodox Christianity, there still lives the idea of theosis, or divination, as the goal of the Christian life. Indeed Orthodox Christian liturgy today may be described as a Christian theurgy, perfectly in tune with the deepest of mysticisms.

For some, the theurgical strain within Neoplatonism begins in Plato’s Symposium. There Socrates relates how the Priestess Diotima staved off a plague by means of sacrifice. Already in place we find a hidden mystical tradition in the initiations of Eleusis. In the fifth century CE, Proclus explains that these initiations do not grant knowledge, but a change of mind. He writes:

“Initiations bring about a sympathy (sympatheia) of souls with the ritual actions in such a way that is incomprehensible to us yet divine, so that some of those initiated are stricken with fear, being filled with divine awe; others assimilate themselves to the holy symbols and, having left their own identity, become completely established in the gods and experience divine possession. 2

Theurgy would eventually come into its full power under the Neoplatonist Iamblichus, born around 245 AD. That was not its beginning however, as Gregory Shaw says,

"Within this esoteric tradition, theurgy was neither an innovation nor a degradation; it was Iamblichus’ attempt to protect the integrity of genuine mystagogy.” 3

Iamblicus himself claimed he was merely following Plato. This may come as a surprise since scholarship until recently tended to ignore the more embodied aspects of philosophy, but as Paul Tyson shows, for the ancients philosophy wasn’t about thinking, which can bring no real truth:

“….right action and right feeling in an actual lived life are clearly a more significant measure of philosophical validity to Plato than smart thinking. Merely intellectually “believing” in the transcendent existence of the form of “The Table” does not make you either a philosopher or a Platonist.

Plato refuses to put his philosophy in clear propositions before us for the very specific reason that he mistrusts written statements as being “dead” propositional substitutes for the communal and individual spiritual practices of the truly philosophical life.

Other than as an active, affective, aesthetic, and embodied existential stance… such spiritual formation cannot be imposed by mere argumentative force and cannot be 'obtained' with a mere proof.

Thus receptive prayer, quiet attention, and right worship are keys to truth and success in the active pursuit of meaningful knowledge.” 4

For Iamblicus the Greek intellectuals had translated traditional mystagogy into sophisticated philosophical concepts, but no longer had the power to transform. For Iamblicus, the gods had to be approached through a specific place in the material world. Sacrifices were not simply ‘sent heavenwards’ but also drew the divinities downwards, specifically by actions and symbols that might invoke those resonances and sympathies which hold the cosmos together. Mysticism for Iamblicus was entirely liturgical.

People have criticized such Pagan practices as low magic, however Iamblichus is insistent that theurgic rites are never intended to change the minds of the gods, rather they bring the practitioner into the divine presence. Why ritual? Because it allows us to resonate with the divine. Iamblicus says,

"…by the practice of supplication we are gradually raised to the level of the object of our supplication and we gain likeness to it by virtue of our constant consorting with it.” 5

Prayer and invocation enacted such bodily and spiritual dispositions to receive more fully the divine flow of grace by way of attunement. The gods need nothing from us, Iamblicus says, therefore it is not about service, as many prior Greek and Roman rituals were. He tells us that,

“…earthly things, possessing their being in virtue of the pleroma of the gods, whenever they come to be ready for participation in the divine, straightway find the gods pre-existing in it prior to their own proper essence.”6

Thus it is not to influence God, but rather to attune ourselves to a greater receptivity of the divine. This involved purification. Although not a terribly sexy subject, ascetic renunciations of the passions, as for Christians, were utterly essential for the Neoplatonists. They followed a triad path of purgation, illumination, and finally union, similar to Christian asceticism. Although it’s true that Iamblicaus with his embracing of matter as a means to the divine is often opposed to Plotinus and his more “disembodied” platonism that attempted to escape the world, David Litwa reminds us,

"For Plotinus, godhood is attained by moral and physical purification, which he conceives of as the removal of everything alien to us. He uses the image of a sculptor who continually chisels off pieces of marble in order to reveal the lovely face of a cult statue within. ” 7

Let’s not forget, also, Porphyry’s attestation to a number of occasions when Plotinus engaged with ritual practices during his daily life, including the famous ‘Séance at the Isium’, when his guardian daimôn was called into visible appearance, only for Plotinus to discover it to be a god.

Prayer too is vital for the ascent of the soul. Proclus tells us,

"It is through prayer that the ascent is brought to completion and it is with prayer that the crown of virtue is attained, namely piety towards the gods…" 8

We become what we worship, and for Christians it is found in Christ Himself, the coinciding resonance of God, binding the temporal to the eternal, man to God, earth to heaven, and the material to the spiritual.

To Western ears, the idea of Christian deification may sound blasphemous, yet it was the common language used in early Christianity. In Eastern Orthodox Christianity it survives still. In St. Dionysius’ own words, he defines theosis as, “Now the assimilation to, and union with, God, as far as attainable, is deification.”

We read the Word became flesh to make us “partakers of the divine nature”(2 Pet 1:4), “He became human that we might become divine” says Athanasius.9 The ancient pagans and Egyptians are ripe with stories of mortals and kings becoming divine. Plato himself was referred to as a god by many Neoplatonists.

The Christian seeks to become one with God, not by discarding his humanity, but by grafting himself onto Christ. Second Temple Jewish literature has many prophets, from Moses to Enoch, becoming winged divine beings, and there are even icons of St John the Baptist with wings. Man is to take over the place of the angels, ruling alongside God in His Divine Council. It is our end and telos to become gods in the very image and form of the dying and risen God Jesus Christ.

Like the Neoplatonists, it is the chanting of scripture and songs of praise that pattern our the Christian soul harmonizing man's being to that of Christ. This is the purpose of fasting, prostrations, and asceticism. St Dionysius tells us that persons have union with God and participate in His likeness “in proportion to their aptitude for deification.” 10

For the Christian, it is from Scripture and historical memory that symbols are taken. For the Neoplatonist, it is objects from nature, the Cosmos as a whole being a divine theophany. Which symbols are more life-giving? Which preserve form most fully? A Christian might point out that St Dionysius, as kind of "Christian Iamblichus" succeeded where Iamblichus himself had failed--in building a theurgic society.

Augustine in The City of God X 9-10 did indeed criticize theurgic practices as mere black magic, however he did so simplistically, and many have pointed out the theurgic strains in his own theology. Gregory Shaw is surely correct when he says,

"Unless we choose to dismiss the role of experience in the rites of the Church, we must follow Dionysius in seeing the liturgy as theurgy, a rite that affects a cognitive, perceptual, and ontological shift so profound in receptive participants that it culminates in theosis , the deification of the soul. For both Iamblichus and Dionysius this deification was effected in rites that united the "fallen" soul with divine activities (ta theia energeia).”

St. Thomas Aquinas describes sacrifice as the act of returning the creature back to its first principle, God, celebrated in the Sacrifice of Praise and the Eucharist. Likewise for Iamblicus the creatures of the material universe are referred back to their divine archetypes during ritual. Iamblicus says,

"The deeds themselves make plain what we hold to be the salvation of the soul: in beholding blessed spectacles the soul acquires another life and operates by another energeia, regarding itself as no longer even human, and rightly so; often indeed, when it has put aside its own life it receives in exchange the most blessed energeia of the gods.” 12

This is not biological life, Bios, but Zoe, a greek term that means the “God-kind of life.” For Christians Christ came to give Zoe spiritual life. "I am come that they might have life (Zoe), and that they might have it more abundantly" (John 10:10). The Christian is not called to change his morality but his being. Literally, like a force, like electricity, we must be remade to exist in a way that continuously receives love (Zoe, spiritual life) that then flows out to others. The Trinity exists this way, an economy of self-giving and receiving, and in Christ's resurrection our human nature that he took on will be grafted onto that circular movement of love we call God.

For the Neoplatonists the philosopher’s task was not to demonstrate that the gods exist, but to recover this knowledge as an active principle, entering into the union with the gods. Iamblicus says,

“That which is divine and intellectual and one in us . . . is then actively aroused in prayers, and when it is aroused it seeks vehemently that which is like itself . . . The gods do not receive prayers through powers or organs, but embrace in themselves the energeiai of pious utterances, especially such utterances as have been established and unified with the gods through sacred rites.” 13

For many Neoplatonists the person in theurgic union with the divine might be considered as a mere receptacle of the god, and so lose their humanity in a sense, at least temporarily. For Christians deification is actually the assumption of our true humanity, as exemplified in Christ. Still, Neoplatonic theory does have some comparisons to the Christian notion of the Incarnation. Gregory Shaw may be exaggerating the similarities, but there are some correspondences, he says,

“The theurgist remains human yet takes the shape of the gods. The language of Chalcedon is remarkably similar. Christ is described as possessing two natures, divine and human, that remain unmixed despite their “union” in the person of Christ. The theurgist also possesses two natures, divine and human, that remain distinct while being embodied by the theurgist.” 14

Both Christianity and Neoplatonism also share a concern with desire. The Christian liturgy, for example, is meant to shape our desire. Our hearts must be educated, both toward what to love and then how best to love it. A person must learn to want a relationship with God. The Christian story is one great love affair. Just so, Gregory Shaw reminds us,

"….for the ancient mystagogues, it is eros—the soul’s primal desire—that deifies us.” 15

Plato writes about the erotic madness that affects the soul’s assent and deification, and Plotinus tells us that all living things, even plants and animals, are carried by their desire for the One.

“Contact with divinity is an erotic, not an intellectual, experience”, Shaw says. 16 As Iamblichus put it, “the Intelligible appears to the mind not as knowable but as desirable.” 17 This erotic presence, Iamblichus said, is “more ancient than our nature” and is awakened in theurgic ritual and prayer. 18 Iamblichus refers to this more ancient principle of the soul in principle of the soul.

A close study will reveal even more similarities. Christians are often criticized for emphasizing their own weakness. In 2 Corinthians 12:9 we read Paul saying:

But he said to me, "My grace is sufficient for you, for my power is made perfect in weakness." Therefore I will boast all the more gladly of my weaknesses, so that the power of Christ may rest upon me.

However, many forget it is only in comparison to God, not other men, that Christians affirm their nothingness. Something like this Christian humility, this emptying of self so that Christ may make His home in the Christian heart, can also be found even in Plato, for whom, in erotic terms, the soul is always poor, ugly, indelicate, homeless, lying on the dirt without a bed. In Plato’s Symposium 203d we find Diotima’s description of Eros, from his mother’s side, portraying the poverty of the human soul. Scholars have noted that it is also a description of the historical Socrates:

“In the first place, he is always poor, and he’s far from being delicate and beautiful (as ordinary people think he is); instead, he is tough and shriveled and shoeless and homeless, always sleeping on the dirt without a bed, sleeping at people’s doorsteps and in roadsides under the sky, having his mother’s nature, always living with Need.” 19

"In plain terms,” says Shaw, “for the gods to become human, the theurgist must remain human, and this means recognizing our weaknesses, our insignificance, our utter nothingness.” 20 Indeed for Iamblicus it is precisely the recognition of our impurity and weakness that allows the gods to become present. He says:

“The awareness of our own nothingness when we compare ourselves to the gods, makes us turn spontaneously to prayer. And from our supplication, in a short time we are led up to that one to whom we pray, and from our continual intercourse we obtain a likeness to it, and from imperfection we are gradually embraced by divine perfection.” 21

Still, one of the most puzzling things for modern people is the very act of ritual itself. The rest of this essay will address the justification of ritual in the soul's spiritual assent to God.

“We taste and feel and see the truth. We do not reason ourselves into it.”

-William Butler Yeats 22

The average Orthodox Christian is most likely ignorant of their own theology. We might ask though, is that a problem? And if so, why? Protestantism has so engulfed the modern imagination that people today cannot imagine a Christianity before the reformation, nor the life practiced in a modern Orthodox Church. Whereas traditional Catholicism found salvation in participating in the sacraments, Protestants would invent a new category of religion based on beliefs, not transformative participatory knowledge, but simple information and assenting to propositions about God.

By the 1700s “Creedal orthodoxy” in the West replaced a living community of social practices. Christianity became a system of beliefs and moral behaviors. This was also compounded by the change from transformative knowledge (being formed into a certain way of being by liturgical attunement) to informative knowledge with the coming of the Gutenberg Press and mass literacy.

Instead of faith being a mode of perception, it became about concepts not resonance, information over initiation. Early Christianity was not primarily about doctrines or dogma, but ritual. You shared a meal with your God, there was a communion, a give and take, perhaps even an exchange of life - your life exchanged for the living Spirit of Christ.

However, Christ did not come to give doctrines, but His body, the Church, and the Orthodox live a faith wherein they are enfolded into His divine body, practicing asceticism in order to receive and share in His Divine life (Zoe).

Modern anthropologists, such as Cathrine Bell, have characterized ritual activities as aiming at generating a socialized agent within a “ritualized body,” which is to say that participation in ritual tends to structure one’s senses, including one’s very “sense of reality.” 23 She says,

"On this understanding, ritual metaphysics is a matter not (or not just) of giving participants a mental image of a larger world, but of giving them the experience of participating in the very patterns and forces of the cosmos. 24 For example, she writes,

“Hence, required kneeling does not merely communicate subordination to the kneeler. For all intents and purposes, kneeling produces a subordinated kneeler in and through the act itself.” 25

Liturgical living is, in fact, not optional. Secular ritual shapes us as surely as any religious ritual. As the anthropologist Talal Asad reminds us, intentional “unbelief” may be just as much the result of “untaught bodies” as it is of untaught (rational) intentionality.

For the Anthropologist Roy Rappaport ritual does not merely identify that which is sacred—it creates the sacred. 26 The sanctifying ritual of holy water, he says, collectively alters the participants’ cognitive schema of water itself, rendering them with a template for differentiating holy water from profane water.

Modern Christianity has been fractured and practice, theology, and poetry broken into separate pieces. Such wholeness can still be found though. The Catholic theologian David W Fagerberg writes of this living wholeness,

“Faith is not mere assent to a doctrine, it is a living relationship to certain events, events that can only be understood (theology) by participating in those mysteries (liturgy). Asceticism is the capacitation for this liturgical state; theology is union with God.” 27

This conception is not absent from the Ancients, David Bradshaw notes that in Platonic theology,

"Faith is in fact the highest member of the so-called Chaldaean triad of love truth, and faith. Just as love joins us to the divine qua beautiful, and truth to the divine qua wisdom, so faith joins us to the divine qua good….

One – and thereby sharing in the divine energeia – is in Proclus no longer conceived as a magical or theurgical rite, save in a very broad sense, but as reaching out to God in love and silent trust. The resemblance on this point between Proclus and Christianity can hardly fail to be noticed.” 28

The Christian liturgical scholar Paul Holmer writes,

“What we know depends upon the kind of person we have made ourselves to be.” 29

Fagerberg adds, “Conversion consists of becoming a new person, learning new passions and training our wants, being re-capacitated, being re-capitulated as we are en-thralled to a new head. There are things that can only be known by becoming a new kind of person.” 30

Thus to be taught how to love is not a matter of being taught certain theories or theological positions, rather Christ through the Church teaches by making His followers into a loving people.There are differences of course. For the Christian liturgy is usually done in a community, whereas Pagan theurgy can be practiced by the individual. It is the community of individuals in relation that properly make Christian persons, and provide the arena to practice the virtues of love.

Many modern people tend to see mere empty ceremonies in the liturgy. It is the individual, they think, who experiences the mystic. This is a false dichotomy. Church liturgy is indeed corporate and symbolic, but it is the individual who experiences the effects, hence liturgical mysticism is personal and spiritualized.

Liturgical mysticism is personal as the mystery of Trinitarian love is produced in an individual person’s soul, but the soul of a liturgical person receives personhood from the corporate, sacramental body which acts upon him or her. The outer liturgy becomes one with the inner liturgy of the heart.

Just as in Platonism, one must ascetically prepare to rightly receive the experience offered by the liturgy. Without asceticism, the world tends to captivate the passions, arousing gluttony and anger, and vainglory. With asceticism, we learn to receive the world as sacrament. Our perceptions always require a prior aesthetic education to receive truth in beauty. Love is necessary first, for love is that essential "mood" capable of receiving Truth once beauty awakens the desire to know it. Only then will the world arouse praise, gratitude, and worship.

Beliefs in fact arise from ritual practices. To become certain of the resurrection, for example, requires more than a movement of the mind. It requires a movement of the heart. Pascal points out that path to belief: “Endeavour, then, to convince yourself, not by increase of proofs of God, but by the abatement of your passions.”31

Fagerberg puts it this way,

“Ascetical mysticism plays liturgical theology in an erotic key by stirring a thirst for truth, beauty, and goodness in a transformed mind that can only be slaked when man’s eros has been purified and straightened in its trajectory.” 32

Divo Barsotti makes a similar point when he writes, “In theology Christianity finds its doctrine, but in liturgical cult Christianity finds its very self. The Church could never be equated with her theology, but she may be equated with her liturgy, because in cult she finds her doctrine and her life, all her doctrine and all her life.” 33

The proper discourse of God is praise, poetry, and song; otherwise we try to cram God into dead concepts. It is by participating in the rhythms of ritual that we order our hearts to receive God. This is the old Christian formula: Right praise = right knowing. Liturgy trains us to see the Truth of God, it forms us into the type of people who can perceive the signs of transcendence all around us.

Hence Iamblichus will say,

“…the invocation makes the intelligence of men fit to participate in the Gods, elevates it to the Gods, and harmonizes it with them through orderly persuasion.” 34

Later he explains,

“…it is the perfect accomplishment of ineffable acts, religiously performed and beyond all understanding, and it is the power of ineffable symbols comprehended by the Gods alone, that establishes theurgical union. . . . In fact, these very symbols, by themselves, perform their own work, without our thinking. . . .” 35

Conclusion

For both Christians and Neoplatonists, human beings are first and foremost lovers. You become what you love, not what you think. Practice, not belief, is primary - our doings precede our thinking.

Thus, God must be sung to be known. It is our practices that liturgically shape disciples into a certain type of people. There are things that only certain types of people can know. For Orthodox Christians and Neoplatonic theurgists, “religion” is about initiation, not information. Religion is a habitus, a disposition of the soul to be in the world a certain way. For both Christians and Pagans, the grammar of God is spoken in communal performance of song, praise, and thanksgiving.

Our present cultural liturgies shape our perception to occlude the presence of wonder and the Divine. This type of knowing requires the preparation of our hearts. Rituals do not express belief, they shape how we know and the liturgy is to form us into the types of people who desire to know God, and then are capable of receiving His spirit. In this sense, I think we can say Orthodox liturgy is indeed a kind of Christian theurgy.

The major difference between Pagan henosis and Orthodox Christian theosis, however, is the person of Jesus Christ. It is in the shape of this God, union with the Triune God, who sacrificed Himself, who became poor and wretched, who became man that we may become god, whose being we are to assume. The difference Christ makes is the very difference of a new Cosmos.

Footnotes

1) Joseph Cardinal Ratzinger, Address to Catechists and Religion Teachers (December 12, 2000), II.3,

2) LIVING LIGHT: DIVINE EMBODIMENT IN WESTERN PHILOSOPHY by GREGORY SHAW

3) ibid

4) Paul Tyson. “Returning to Reality: Christian Platonism for Our Times” pg 130

5) Iamblicus, On the Mysteries, (I. 15 pp. 58-61).Emma C. Clarke, Society of Biblical Literature (November 1, 2003)

6) ibid, (I.8. pp. 36-7)

7) M. David Litwa. Becoming Divine: An Introduction to Deification in Western Culture, pg 108

Eugene, Oregon: Cascade Books, 2013.

8) Proclus, '𝘖𝘯 𝘵𝘩𝘦 𝘗𝘳𝘪𝘦𝘴𝘵𝘭𝘺 𝘈𝘳𝘵' [𝘋𝘦 𝘚𝘢𝘤𝘳𝘪𝘧𝘪𝘤𝘪𝘰 𝘦𝘵 𝘮𝘢𝘨𝘪𝘢] 148.1-18, trans. Copenhaver, 1988, p.103.

9)Athanasius On the Incarnation 54.

10) Dionysius the Areopagite, Works (1899) vol. 2. p.67-162. The Ecclesiastical Hierarchy

11) Neoplatonic Theurgy and Dionysius the Areopagite (Journal of Early Christian Studies, Winter, 1999)Gregory Shaw

12) ibid (i.12.41).

13) (i.15.46–47) DeMysteriis

14) Shaw, Theurgy and the Soul, 57, cf. 53-57.

15) LIVING LIGHT: DIVINE EMBODIMENT IN WESTERN PHILOSOPHYGregory Shaw

16) ibid

17 ) Cited by Damascius, Traité des Premiers Principes II, text and translation by L.G.

18), Dm 270.9, and “the one in us”, Dm 46.13.

19 Plato, Symposium, translated with introduction and notes by A. Nehamas and P. Woodruff (Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing Co., 1989).

20) DIVINE EMBODIMENT IN WESTERN PHILOSOPHy by Gregory Shaw

21) Myst. 47.13-48.4

22) Yeats, Memoirs, 1972, p.195-96

23) Bell, C. Ritual Theory, Ritual Practice. New York: Oxford University Press. (1992:80, 221)

24) ibid (1992:160 n.206)

25) ibid 100-101.

26) Ritual and Religion in the Making of Humanity. By Roy A. Rappaport. Cambridge Studies in Social and Cultural Anthropology

27) Liturgical mysticism by David W. Fagerberg, pg 108 Emmaus Academic (December 27, 2019)

28) pg 152 Aristotle East and West: Metaphysics and the Division of Christendom Cambridge University Press; 1st edition (March 26, 2007)

29 Paul Holmer, C. S. Lewis: His Life and His Thought (New York: Harper & Row, 1976), 90.

30, Liturgical mysticism by David W. Fagerberg, pg 208 Emmaus Academic (December 27, 2019)

31) Blaise Pascal, Pensees tr. by WE. Trotter (Mineola, NY: Dove Philosophical Classics, 2003), #233, pp. 65-69.

32) David Fagerberg Provisions for the Journey February 4, 2020, St Paul Center for Biblical Theology

33) Divo Barsotti, Il mistero Cristiano nell’anno liturgico (1951; Cinisello Balsamo, Italy: San Paolo Edizioni, 2006); in English as The Christian Mystery in the Liturgical Year

34) (DM 42.9-15)

35) (DM 96.17-97.6)