Here’s an excerpt form Bruce Folz’s superb book the Noetics of Nature :

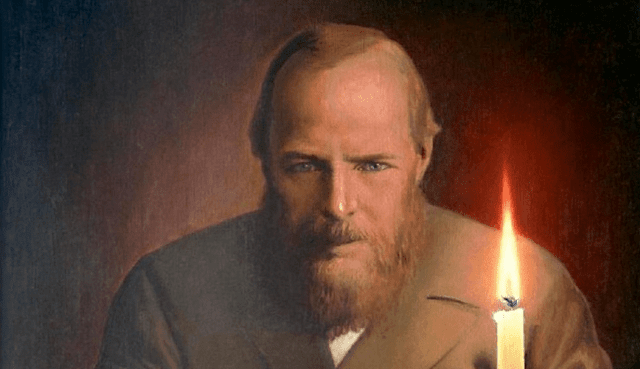

Within a twenty-year period, from the early 1870s to the late 1880s, both Nietzsche and Dostoevsky were preoccupied with the question of European nihilism. Both regarded nihilism as involving a misrelation to the earth, both saw the question of divine transcendence as a key to understanding it, and both saw the overcoming of nihilism as having an aesthetic dimension. Their diagnoses, however, are diametrically opposed, and it is not surprising that the analysis of Nietzsche, the self-avowed “good European” whose thought is deeply rooted in modern European concerns, should have been embraced one-sidedly in Western intellectual circles, to the near exclusion of Dostoevsky’s diagnosis, which looks at Western nihilism from the East.

But if this scholarly imbalance is not surprising, neither is it felicitous, especially with regard to understanding the relationship of environmental crisis to contemporary nihilism. Both diagnoses, it could be argued, proceed from the Western over-emphasis on divine transcendence that has been discussed previously. But whereas Nietzsche’s Zarathustra exhorts us to be true to the earth by rejecting transcendence altogether, Dostoevsky’s most prophetic characters in his later novels commend a vision of the earth as once again infused with the transcendent, a vision of the earth as sacramental and iconic.

Redemption for Nietzsche can be seen as the work of human creators willing to assume the place of God. Whereas for Dostoevsky it calls for the rejection of this same modern project of attempting to create self and world (and whose disastrous, abortive effects are studied in Devils), and calls instead for seeking, in repentance and humility, the image of divine beauty in humanity and in nature, as exemplified in The Brothers Karamozov by Alyosha and by the Elder Zosima—Dostoevsky’s rendering of the actual St. Tikhon of Zadonsk.

In Devils, previously translated as The Possessed, and whose final installment was published in 1873, nihilism is presented as consisting of interrelated negations: the denial of transcendence, contempt for the life of the peasants, and a disdain for the earth. (Shatov’s injunction to the arch-nihilist and smug child-molester Stavrogin: “‘Kiss the earth, flood it with tears, ask forgiveness! . . . acquire God by labor; the whole essence is there, or else you’ll disappear like vile mildew; do it by labor . . . peasant labor. Go, leave your wealth.’ ”) In A Writer’s Diary, the July and August entries of 1876 include a section called “The Land and Children.”

In Devils, previously translated as The Possessed, and whose final installment was published in 1873, nihilism is presented as consisting of interrelated negations: the denial of transcendence, contempt for the life of the peasants, and a disdain for the earth. (Shatov’s injunction to the arch-nihilist and smug child-molester Stavrogin: “‘Kiss the earth, flood it with tears, ask forgiveness! . . . acquire God by labor; the whole essence is there, or else you’ll disappear like vile mildew; do it by labor . . . peasant labor. Go, leave your wealth.’ ”) In A Writer’s Diary, the July and August entries of 1876 include a section called “The Land and Children.”

Dostoevsky anticipates Aldo Leopold and Wendell Berry here in arguing that we need to live closer to the land, maintaining that the earth is “sacramental,” introducing the theme of the earth as Paradise or “Garden,” and insisting that children “should be born and arise on the land, on the native soil in which its grain and its trees grow.” And in the April entries of the following year, he publishes serially his remarkable short story, “The Dream of a Ridiculous Man,” termed by Mikhail Bakhtin an “encyclopedia of Dostoevsky’s most important themes.”

The story commends to the reader a “living image” of the earth as paradise—of an earth “which seemed to have a festive glow, as if some glorious and holy triumph had at last been achieved” (i.e., a vision of what we have called the iconic earth). Not only do its inhabitants love one another, they also love the earth, singing hymns of “nature, the earth, the sea, and the forests,” and conversing with the very trees with an “intensity of love.” “They regarded the whole of nature in the same way [as the trees]—the animals, which lived peaceably with them and did not attack them, conquered by their love” and the stars as well. The dreamer relates how in homage to this unfallen world, he “kissed the earth on which they lived.” On awakening, however, he realizes that this “living image” of paradisiacal earth is not just a dream but “the truth,” and that it could be realized “at once” if we truly wanted it.

In The Brothers Karamazov, completed three years later, Dostoevsky felt that he had finally arrived at a statement that pointed beyond the nihilism which threatened not only Western Europe but the entire earth. Here he develops the themes of the preceding works extensively and powerfully, elaborating them explicitly within the sphere of Orthodox spirituality, and thus only a very brief and general characterization of them is possible here.

Presenting his final teaching, the Elder Zosima recalls how his adolescent brother had undergone a wondrous change as he neared an untimely death. Remorseful over his previous bitterness and cynicism, yet weeping with joy, he asks for forgiveness even from the birds singing outside his window:

“Birds of God, joyful birds, you, too, must forgive me, because I have also sinned before you . . . Yes . . . there was so much of God’s glory around me: birds, trees, meadows, sky, and I alone lived in shame, I alone dishonored every- thing, and did not notice the beauty and glory of it all.”

Awakened, his eyes opened, he now sees that “life is paradise, but we do not want to know it, and if we did want to know it, tomorrow there would be paradise the world over.”Thus, a kind of nihilistic unbelief prevented him from seeing the paradisiacal glories of the nature around him, and only when he repented of this were his eyes open. Zosima then relates how he himself, repenting of pride that had brought him to the brink of a duel, had cried out with a new aware- ness: “Look at the divine gifts around us: the clear sky, the fresh air, the tender grass, the birds, nature is beautiful and sinless, and we alone, are godless and foolish and do not understand that life is para- dise, for we need only to wish to understand, and it will come at once in all its beauty.”

The Elder goes on to deliver a series of “talks and homilies” to his closest friends and students. In these, he presents his understanding of the dangers of Western nihilism and of the iconic vision that can overcome it. He warns against scientific materialism, which distorts the image of God in nature; against the moral relativism that he sees engendered by science; against the acquisitive materialism, individualistic hedonism, and “spiritual suicide” of the newly wealthy; and against the age’s rejection both of “the spiritual world” and of “the idea of serving mankind, of the brotherhood and oneness of people.” Exhorting repentance of this nihilistic mindset, he urges instead love not only for other people but for nature as well, in an admonition that could well serve as the quintessential environmentalist sermon, and that explicitly evokes the epigram from St. Isaac of Syria—whose Ascetical Homilies became Dostoevsky’s companion— that stands at the beginning of the chapter:

Brothers, do not be afraid of men’s sins, love man also in his sin, for this likeness of God’s love is the height of love on earth. Love all of God’s creation, both the whole of it and every grain of sand. Love every leaf, every ray of God’s light. Love animals, love plants, love each thing. If you love each thing, you will perceive the mystery of God in things. Once you have perceived it, you will begin tirelessly to perceive it more and more of it every day. And you will come at last to love the whole world with an entire, universal love. Love the animals: God gave them the rudiments of thought and an untroubled joy.

The Elder goes on to deliver a series of “talks and homilies” to his closest friends and students. In these, he presents his understanding of the dangers of Western nihilism and of the iconic vision that can overcome it. He warns against scientific materialism, which distorts the image of God in nature; against the moral relativism that he sees engendered by science; against the acquisitive materialism, individualistic hedonism, and “spiritual suicide” of the newly wealthy; and against the age’s rejection both of “the spiritual world” and of “the idea of serving mankind, of the brotherhood and oneness of people.” Exhorting repentance of this nihilistic mindset, he urges instead love not only for other people but for nature as well, in an admonition that could well serve as the quintessential environmentalist sermon, and that explicitly evokes the epigram from St. Isaac of Syria—whose Ascetical Homilies became Dostoevsky’s companion— that stands at the beginning of the chapter:

Brothers, do not be afraid of men’s sins, love man also in his sin, for this likeness of God’s love is the height of love on earth. Love all of God’s creation, both the whole of it and every grain of sand. Love every leaf, every ray of God’s light. Love animals, love plants, love each thing. If you love each thing, you will perceive the mystery of God in things. Once you have perceived it, you will begin tirelessly to perceive it more and more of it every day. And you will come at last to love the whole world with an entire, universal love. Love the animals: God gave them the rudiments of thought and an untroubled joy.

Do not trouble it, do not torment them, do not take their joy from them, do not go against God’s purpose. Man, do not exalt yourself above the animals: they are sinless, and you, you with your grandeur, fester the earth by your appearance on it, and leave your festering trace behind you . . . My young brother asked forgiveness of the birds: it seems senseless, yet it is right, for all is like an ocean, all flows and connects; touch it in one place and it echoes at the other end of the world. Let it be madness to ask forgiveness of the birds, still it would be easier for the birds, and for a child, and for any animal near you, if you yourself were more gracious than you are now, if only by a drop, still it would be easier. All is like an ocean, I say to you. Tormented by universal love, you, too, would then start praying to the birds, as if in a sort of ecstasy, and entreat them to forgive you your sin. Cherish this ecstasy, however senseless it may seem to people. My friends, ask gladness from God. Be glad as children, as birds in the sky.

Seyyed Hossein Nasr have blamed our present environmental crisis on our Western establishment of the first truly secular culture the world has known. Nasr calls for a “resacralization of nature, not in the sense of bestowing sacredness upon nature, which is beyond the power of man, but of lifting aside the veils of ignorance and pride that have hidden the sacredness of nature from the view of a whole segment of humanity.”

And Sherrard calls for a recovery of “our capacity to perceive this symbolic function of natural things—to perceive the numinous presence of which each natural form is the icon—that [was] increasingly eclipsed by those intellectual developments that took place in the Christian, and hence by and large European, consciousness in the later medieval period.”107 For Sherrard and Nasr, the modern West is anomalous and apostate from the otherwise shared experi- ence and wisdom of humankind according to which, in the words of Elder Zosima, this world “lives and grows only through its being in touch with other mysterious worlds.”

No comments:

Post a Comment