For all his brilliant insights, both philosophical and psychological, Nietzsche was a failure as a man, on his own terms, he failed to appreciate the full horror of human suffering.

For although he envisions redemption as being achieved by some almost super-human act of heroic affirmation, ‘Yes saying’ to life in all its horrific fulness, the truth, according to Giles Fraser, is that Nietzsche’s conception of horror, of suffering and indeed of the nihil itself are the imaginings of the comfortably off bourgeoisie. ‘An armchair philosopher of human riskiness’ is what Martha Nussbaum has called him,

The following excerpts are taken mostly from Fraser’s Pious Nietzsche, noting Nietzsche's extreme individualism, he writes,

“Indeed, isn't his `kind of denial of an existence shared with others' linked to `the murderous lengths to which' Nietzsche will go in order to repress the claim the other has upon him? Could it be that Nietzsche's unwillingness to enter into the suffering of another, that is, his objection to the empathic projection involved with pity, represents an unwillingness not simply to see, but to be seen? Karl Barth seems to be tracking Nietzsche down in precisely this way when he writes:

"And the true danger of Christianity . . . on account of which he had to attack it with unprecedented resolution and passion . . . was that Christianity - what he called Christian morality - confronts the real man, the superman . . . with a form of man which necessarily questions and disturbs and destroys and kills him to the very root. That is to say, it confronts him with the figure of the suffering man. It demands that he should see this man, that he should accept his presence, that he should not be man without him but man with him, that he must drink with him at the same source. Christianity places before the superman the Crucified, Jesus, as the Neighbour, ignoble and despised in the eyes of the world (of the world of Zarathustra, the true world of men), the hungry and thirsty and sick and captive, a whole ocean of human meanness and painfulness. Nor does it merely place the Crucified and his host before his eyes. It does not merely will that he see Him and them. It wills that he should recognise in them his neighbours and himself."

For Barth, what Nietzsche feared in the other was a reflection of his own suffering humanity. Nietzsche preferred fantasies of (super-human) strength and self-sufficiency to the recognition of human-all-too-human need and fragility. Throughout Zarathustra, Nietzsche's hero is haunted by the crippled dwarf, the little man, the small man. In one of the great emotional climaxes of Thus Spoke Zarathustra, as Zarathustra comes to feel the full force of eternal recurrence, that is, as he is faced with the reality of what he can and cannot affirm about himself, it is the weight of the dwarf (note especially that Nietzsche speaks of the eternal recurrence as `the greatest weight') that restricts his full self-affirmation. In the climax of the passage Zarathustra turns on the dwarf: `Dwarf! You! Or I!'

Stanley Rosen interprets this exclamation in this way: `The immediate sense of the image is as follows. Zarathustra can rise no higher until he overcomes the pity for humanity that still pulls him back to the earth below.' In this way Nietzsche's rejection of pity (in so far as Nietzsche and Zarathustra are of a common mind at this point) represents a rejection of, a refusal to acknowledge, any sense of identity between himself and the crippled dwarf figure, suffering humanity. Better to murder the dwarf, to oust him, to sacrifice him even, than to have him make me face my own dwarfness - thus spoke Zarathustra. In rejecting suffering humanity, in casting people as the herd, Nietzsche is seeking to set himself free from the earth below. This begins Nietzsche's disloyalty to the earth; a 'murderous' disloyalty which, for all Nietzsche's emphasis on honesty, is motivated by an unwillingness fully to face the pains and disappointments of his own humanity.

Nussbaum, for instance, accuses Nietzsche of having a specifically bourgeois conception of pain (a suggestion that would have been deeply threatening for Nietzsche):

We might say, simplifying things a bit, that there are two sorts of vulnerability: what we might call bourgeois vulnerability – for example, the pains of solitude, loneliness, bad reputation, some ill health, pains that are painful enough but still compatible with thinking and doing philosophy – and what we might call basic vulnerability, which is the deprivation of resources so central to human functioning that thought and character are themselves impaired and not developed. Nietzsche focuses on the first sort of vulnerability, holds that it is not so bad; it may even be good for the philosopher. The second sort, I claim, he merely neglects.

Nussbaum argues that, for all Nietzsche’s posturing about the needs and importance of the body and the physical, he fails to notice the obvious; basic bodily needs, and the pains associated with such needs not being met.

Does Nietzsche have to say about hunger? about being cold? about homeless- ness? about earning a living or bringing up a family? ‘Who provides basic welfare support for Zarathustra? What are the “higher men” doing all the day long? The reader does not know and the author does not seem to care.’ All of this, one might say, develops out of a ressentiment against ‘ordinary’ life. Nussbaum concludes:

"Nietzsche is really, all along, despite all his famous unhappiness, too much like the ‘famous wise men’: an armchair philosopher of human riskiness, living with no manual labour and three meals a day, without inner understanding of the ways in which contingency matters for virtue.

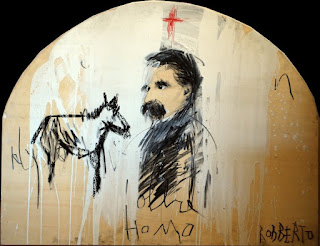

Nietzsche famously gives his vision of “salvation” in a fable about a camel, representing guilt burdened slavish everyman, who transforms into a mighty lion, saying NO to society’s moral systems and YES to his own ability to create new values, to, finally, an innocent child.

And yet here is Nietzsche premising his whole vision of salvation upon the new beginning of childhood. Nietzsche, it seems, takes the ‘born again’ metaphor more literally than was intended.Michael Tanner writes:

That phrase ‘a new beginning’ is dangerous. For it is usually Nietzsche’s distinction as a connoisseur of decadence to realise that among our options is not that of wiping the slate clean. We need to have a self to overcome, and that self will be the result of the whole Western tradition, which it will somehow manage to ‘aufheben’, a word that Nietzsche has no fondness for, because of its virtual Hegelian copyright, and which means simultaneously ‘to obliterate’, ‘to preserve’ and ‘to lift up’. Isn’t that just what the Übermensch is called upon to do, or if we drop him, what we, advancing from our present state, must do if we are to be ‘redeemed’?

Nietzsche’s recourse to the image of the child suggests a point of fundamental weakness in his overall salvation story.

One can understand the theory, but not how that theory can be implemented. It is like saying the prostitute can only be redeemed by virginity. One can see what that might mean metaphorically but not how it is possible in practice.

In this respect, Christianity operates a far more realistic sense of what it is to be redeemed. For the Christian, redemption is made possible by repent- ance and forgiveness. And while Nietzsche castigates this model as the very engine of ressentiment (asking one to view one’s past as sinful), the advantage it does have over Nietzsche’s alternative is that it is realistic enough to recognise that for salvation to be human salvation it must incorporate and face up to our past as well as our present. While Christianity requires repentance of one’s past the child image suggests its complete annihilation. And surely this represents a species of denial (a refusal to ‘face up to’) no less susceptible to the workings of ressentiment.

But if this is the case the child image breaks down completely, for surely the child represents the ultimate ‘No-saying’ to one’s past since, obviously enough, the child does not have a past. To be born again as a child is to born again as an amnesiac.

Another disturbing feature of Nietzsche’s celebration of the child is the idea that total unselfconsciousness is a sign of spiritual excellence. Nietzsche makes this point on a number of occasions. In a note recorded in The Will to Power he writes of ‘the profound instinct that only automatism makes possible perfection in life and creation’. Similarly in The Anti-Christ, when celebrating the spirituality of the Manu Law-Book, he writes:

"The higher rationale of such a procedure lies in the intention of making the way of life recognised as correct (that is demonstrated by a tremendous amount of finely-sifted experience) unconscious: so that a complete automatism of instinct is achieved – the precondition for any kind of mastery, any kind of perfection in the art of living."

Heller argues that Nietzsche’s idea that an unselfconscious automaton represents some sort of redeemed condition is forced upon him by his overly developed suspicion of all belief: ‘What haunted Nietzsche . . . was the pervasive suspicion that the self-consciousness of the intelligence had grown to such a degree as to deprive any belief of its genuineness.’Nietzsche speaks of ‘man’s ability to see through himself and history’ as something too well- developed to out-wit.And though it is precisely this talent for suspicion that has won out over Christianity, the price of that victory is the release of a corrosive spirit that no belief can possibly survive. Nietzsche’s capacity to knock down has thus exceeded his capacity to build up and he is consequently left, as he thinks Christianity is left, celebrating nothingness. For how different is the lobotomised automaton to the anesthetised Christian?

Indeed the idea that unselfconsciousness constitutes some sort of redemption sounds a little like the logic of the drunk for whom redemption is found in a bottle. But perhaps, by developing the capacity for suspicion above all else, Nietzsche has made the search for redemption impossibly difficult, so there seems little else but to retreat into drunkenness. And such is the intelligence of the drunk that he continues to persuade himself that salvation is to be found in that which helps him forget his failure (hence Nietzsche’s frequent celebration of forgetfulness).”

Nietzsche saw life as an art, a way to be truthful, and, if so, kitsch the, is art that is a lie, it wholly distorts reality by denying the perspective of the afflicted, by denying the horror, by denying shit. Kitsch is a beautifying gloss, and as a gloss a strategy of denial. As Kundera defines it ‘kitsch is the absolute denial of shit’

This idea that the problem with kitsch is that it fails to speak the truth, that it is insufficiently honest, that it prefers, wherever possible, sentimental fantasy to painful reality.

But, says Fraser, “…it is precisely through his depiction of pain and suffering that Nietzsche is most disposed to kitsch, then Nietzsche is shown to be a most dangerous thinker; one who writes of suffering in such a way that much of the reality of suffering is actually hidden.

For in tending towards the general and the abstract philosophy becomes intrinsically disincarnate. Human suffering, on the other hand, is always the suffering of a particular person at a particular moment in time.

Of course Nietzsche is hailed as resisting the metaphysical imperative to generalise wherever possible, but this instinct is preserved in his preference for dealing in types and tropes. The characters in Zarathustra always stand for generalised approaches to the world. They are little more than sophisticated cartoons representing types of human failure or weakness. Zarathustra himself has no history, no wider context. We do not find it appropriate to ask of his child- hood or of his sexuality because Zarathustra only exists to the extent that he expresses the twists and turns of Nietzsche’s spiritual journey. In such a milieu authentic thinking about suffering becomes all but impossible. For any thinking about suffering that does not attend to its incarnation thinks only the idea of suffering, that is suffering without pain.

For Christians the success of the attempt to think through the nature of suffering is bound up with the story of a particular person at a particular moment in time. Philosophy, of course, condemned this particularity as a scandal. However, I would argue that, precisely because of this attitude, philosophy is unable to generate a genuine encounter with the necessary particularity of human pain.

For in seeking to express suffering philosophically Nietzsche takes suffer- ing away from its locatedness in particular contexts and stories, thereby rendering it kitsch. When Zarathustra ascends to his mountain top he leaves the shittiness of the world far behind.

My overall objection to Nietzsche is that he glamorises suffering. His sense that suffering has the capacity to edify the noble spirit is only possible from the perspective of one who knows not the destructive power of excremental assault. Following the holocaust, Nietzsche’s prescriptions for redemption can only be looked on as those of a more comfortable age. The holocaust re-defines nihilism in such a way that Nietzsche’s strategy for overcoming it is rendered obsolete.

Does Christianity fare any better than Nietzsche in its capacity to encounter human suffering?

It is symbolically important that Christ was born in a stable, amid the stench and mess of animal dung (though, all too often, the nativity scene is imag- ined all cleaned up – and this act of cleaning it up is precisely the begin- nings of Christian kitsch). The prima facie offensiveness of the intimate juxtaposition God/shit recaptures something of the original offensiveness of the incarnation itself, which offence, incidentally, points to Athens and not Jerusalem as the original purveyor of kitsch. Neitzche mistakes(and hellenised Zoroastrianism) with authentic Christianity, Ultimately nothing is less kitsch than the idea of the crucifixion (Kundera has also described kitsch as ‘a folding screen to curtain off death’; that is, kitsch cannot face death, still less one as horrific as crucifixion).

The power of Good Friday is that as He is crucified Jesus meets and takes upon Himself the full horror and darkness of the world. The fulcrum of Christian soteriology is the point at which God and ‘shit’ meet.

For Girard, what Nietzsche is pointing out is the way in which the instinct for vengeful reciprocity continues to assert itself when violent retribution is denied. I may respond to your striking me by turning the other cheek, but in my guts I still want to punch you back. That instinct may, of course, have all sorts of morally significant consequences, and Nietzsche is right to point them out. But even so, such consequences are surely a price worth paying for calling a halt to retributive violence. Girard puts it thus:

“Ressentiment is the interiorisation of weakened vengeance. Nietzsche suf- fers so much from it that he mistakes it for the original and primary form of vengeance. He sees ressentiment not merely as the child of Christianity, which it certainly is, but also as its father, which it certainly is not. Ressentiment flourishes in a world where real vengeance (Dionysus) has been weakened. The Bible and the Gospels have diminished the violence of vengeance and turned it to ressentiment not because they originate in the latter but because their real target is vengeance in all its forms, and they succeeded in wounding vengeance, not eliminating it. The Gospels are indirectly responsible; we alone are directly responsible. Ressentiment is the manner in which the spirit of vengeance survives the impact of Christianity and turns the Gospels to its own use.

Ressentiment is what is left of vengeance once one sets out on the road for peace. Nietzsche is at his best in seeking out and revealing the instinct for vengeance that hides behind the false Christian smile or the pathos of the victim. In times of peace and prosperity it is easy to miss the bigger picture and confuse this interiorised weakened vengeance with the real thing."

Girard continues:

“Nietzsche was less blind to the role of vengeance in human culture than most people of his time, but nevertheless there was blindness in him. He analysed ressentiment and all its works with enormous power. He did not see that the evil he was fighting was a relatively minor evil com- pared to the more violent forms of vengeance. His insight was partly blunted by the deceptive quiet of his post-Christian society. He could afford the luxury of resenting ressentiment so much that it appeared a fate worse than real vengeance. Being absent from the scene, real vengeance was never seriously apprehended. Unthinkingly, like so many thinkers of his age and ours, Nietzsche called on Dionysus, begging him to bring back real vengeance as a cure for what seemed to him the worst of all possible fates, ressentiment.”

Nietzsche and the Stoics.

A number of commentators use the following example: returning home to find his house on fire and his child inside, the Stoic sage seeks to save the child from the flames – because that is the virtuous thing to do. If, however, he is unable to save his child the Stoic sage will have no regrets. This for three reasons: ‘First, because the sage did the right thing . . . Second because death is not an evil but an “unpreferred indifferent” . . . And, third, every- thing that happens is ordered for the best by Providence.’ It is interesting to note, with Nietzsche in mind, that the ‘hardness’ of Stoicism is connected with a cosmological view which enables the sage to treat with equal affirmation whatever Providence might bring, even the death of a child. This is is the sort of state Nietzsche believes is suggested by the eternal recurrence: an affirmation of life in its totality, so-called tragedies and all. And it is no coincidence that the Stoics (arguing from the impossibility of a ‘first cause’) themselves believed that history endlessly repeated itself in identical cycles.

Giles Fraser comments,

“Here, then, is another way of breaking the cycle of violence and vengeance. What is to be made of it? Firstly, surely this: it must be the case that this sort of ‘hardness’ is some unrealistic fantasy. Can the Stoic sage really remain indifferent to the screams of his burning child? And if he does, if indeed he is prepared to affirm these screams as a necessary condition of the full affirmation of life, surely he is not to be admired. Nussbaum argues that the ‘hardness’ of the Stoics and Nietzsche is a symptom of their weakness, not of their strength. It is the ‘hardness’ of one who wishes to become, or fantasises he can become, something other than (more than? less than?) human. Deafness to the screams of the child is the deafness of one who has lost sight of humanity. Nussbaum argues:

“Finally, we arrive at what perhaps is the deepest question about the anti- pity tradition: is its ideal of strength really a picture of strength? What should we think about a human being who insists on caring deeply for nothing that he does not control . . . who cultivates the hardness of self- command as a bulwark against all the reversals that life can bring? We could say, with Nietzsche, that this is a strong person. But there is clearly another way to see things. For there is a strength of a specifically human sort in the willingness to acknowledge some truths about one’s situation: one’s mortality, one’s finitude, the limits and vulnerabilities of one’s body, one’s need for food and drink and shelter and friendship . . . There is, in short, a strength in the willingness to be porous rather than totally hard, in the willingness to be a mortal animal living in the world. The Stoic, by contrast, looks like a fearful person, a person who isdetermined to seal himself off from risk, even at the cost of the loss of love and value . . . He fails, that is, to see what the Stoicism he endorses has in common with the Christianity he criticises, what ‘hardness’ has in common with otherworldliness: both are forms of self-protection, both express a fear of this world.”

Nussbaum thereby charges the anti-pity tradition with a disloyalty to the earth; a cardinal crime in Nietzsche’s book, of course.

For all his condemnation of religious asceticism, Nietzsche continually sought out the habitat of monks; the empty wilderness or the solitude of the mountaintop. His whole energy seeks the cultivation of the individual self a cultivation that is premised upon a sense of scrupulous honesty about his own spiritual journey.

But is it, in the end, really possible to be fully honest about oneself without being honest about others and with others? What of the idea that many of us ‘become who we are’ in and through a relationship with others? What of the idea that relationships make possible (and require) a level of honesty about oneself that is not possible in isolation? If so, then Nietzsche’s self-focus, for all its inten- sity, may turn out to be a strange form of dishonesty. A dishonesty which, as Nussbaum suggests, is motivated by a fear of vulnerability, of dependency, of not being fully in control.

Stanley Cavell uses ‘skepticism’ as a way of confronting what one might call the ‘problem of the other’. And this so- called ‘problem’ is not simply, or even primarily, a philosophical concern,

According to Cavell, the problem with the skeptic’s position is that it is a displaced and misplaced expression of a fundamental and genuine human concern.

Cavell argues that what is going on in thinking such as this is a translation of the complex demands of social intercourse into the language of philosophy, thus effectively de-problematising the emotionally sensitive questions of human contact by rendering them metaphysical or philosophical. In a sense, skeptical philosophy avoids the more difficult, one might say human-all-too-human ‘problem of the other’, by making the uncertainty inherent within human contact some sort of philosophical puzzle to be solved intellectually.

Thus Cavell writes:

"In making the knowledge of others a metaphysical difficulty philosophers deny how real the practical difficulty is of coming to know another person, and how little we can reveal of ourselves to another’s gaze, or bear of it. Doubtless such denials are part of the motive which sustains metaphysical difficulties.

The sense of a gap that divides us from our fellow human beings is generated by a desire to avoid the vulnerabilities, the openness and consequent risk, inherent within genuine human encounter. As one commentator has put it: ‘Our turning from others – and not, say, simply being uncertain about them – points to something in us (shame, for example, or embarrassment) and not something missing in them.’ Cavell dubs this ‘avoidance’.

Michael Fisher claims that ‘In Cavell’s account, the skeptic deprives himself of our ordinary links with the world and each other and then tries – unsuccessfully – to repair those links all by himself.’

Nietzsche’s outcasting is shown to issue from a certain sort of fear.

Nietzsche writes in Ecce Homo: ‘At an absurdly early age, at the age of seven, I already knew that no human word would ever reach me.”

On his desperate need for the comfort of another:

"The last philosopher I call myself, for I am the last human being. No one converses with me beside myself and my voice reaches me as the voice of one dying. With the beloved voice, with thee the last remembered breath of human happiness, let me discourse, even if it is only for another hour. Because of thee I delude myself as to my solitude and lie my way back to multiplicity and love, for my heart shies away from believing that love is dead. I cannot bear the icy shivers of loneliest solitude. It compels me to speak as though I were Two.”

Nietzsche’s answer to loneliness was to imagine himself as two persons who can then comfort each other. Nietzsche became his own imaginary friend.

Fraser continues,

“The Pietist rejection of all that stands over against the sovereign human individual, its rejection of any authority other than the authority of the human heart, made a lasting impression upon Nietzsche. And Nietzsche’s ultimate rejection of God is nothing less than a continuation of Pietist logic; either God can be sucked into, and put in the service of, the human will, or God has to be destroyed. It wasn’t so much that God had to die in order for humanity to flourish (as so many followers of Nietzsche understand him to be saying) but that God had to die in order for the individual to assume what had been hitherto divine sovereignty.

Nietzsche claimed for the individual the place traditional Christianity had ascribed to God: ‘The “ego” subdues and kills: it operates like an organic cell: it is a robber and violent. It wants to regenerate itself – pregnancy. It wants to give birth to its god and see all mankind at his feet.’

Luce Irigaray (picking up the image of birthing) puts it another way. In setting up an imaginary dialogue with Nietzsche, and accusing him of ressentiment against life and specifically a ressentiment against women (as having a ‘womb-envy’ expressed in his desire to give birth to himself), she writes:

“To overcome the impossible of your desire – that surely is your last hour’s desire. Giving birth to such and such a production, or such and such a child is a summary of your history. But to give birth to your desire itself, that is your final thought. To be incapable of doing it, that is your highest ressentiment. For either you make works that fit your desire, or you make desire itself into your work. But how will you find material to produce such a child? And going back to the source of all your children, you want to bring yourself back into the world. As a father? Or child? And isn’t being two at a time the point where you come unstuck? Because to be a father, you have to procreate, your seed has to escape and fall from you. You have to engender suns, dawns, twilights other than your own.

But in fact isn’t it your will, in the here and now, to pull everything back inside you and to be and to have only one sun? And to fasten up time, for you alone? And suspend the ascend- ing and descending movement of genealogy? And to join up in one perfect place, one perfect circle, the origin and end of all things?”

This is a stunning (though perhaps characteristically, somewhat oblique) passage. Irigaray’s point and the argument that Nietzsche seeks and fails to find self-salvation are, at base, quite the same. Nietzsche’s attempt to give birth to himself is the ultimate logical consequence of his atheistic evangelicalism; that is, of his desire to be ‘born again’ but not ‘born from above’. “

Self-exposure is resisted even if it means (and it always does) that one has to deny, or refuse to acknowledge, another. The power of the resistance to self- exposure is such that one would rather will madness or the death of loved ones than be exposed.

In rejecting suffering humanity, in casting people as the herd, Nietzsche is seeking to set himself free from the earth below. This begins Nietzsche’s disloyalty to the earth; a ‘murderous’ disloyalty which, for all Nietzsche’s emphasis on honesty, is motivated by an unwillingness fully to face the pains and disappointments of his own humanity.

Truth can be had for Nietzsche by tough-minded determination, by a rigorous exercise of suspicion. But this suspicion, when pursued as an absolute demand, forecloses upon dimensions of honesty available only to those who are prepared to accept and trust the love of another. The one who is loved is more able to face the reality of their own pain and sense of worthlessness because admitting and facing all of that no longer seems so cataclysmic.

Only thus is the wisdom of Silenus fully defeated. Williams sums up: ‘Truth makes love possible; love makes truth bearable.’

No comments:

Post a Comment